Elric

Well-Known Member

How Gun-Barrels Are Straightened.

By William H. Avis.

American Machinist, July 13, 1905, pages 44-45

https://books.google.com/books?id=x...=onepage&q=Line straightening barrels&f=false

It is conceded by gunmakers that the most difficult part of a gun to make is the barrel. If the interior of the barrel is incorrect the whole gun is liable to prove worthless. This does not necessarily mean that the bore must be absolutely perfect. But the nearer the workmanship approaches that standard the better. It is true that a barrel can sometimes be more or less defective and shoot very accurately; but this is the exception and not the rule. Defective articles, of whatever description, are not apt to be sought after, nor can they be depended upon; in fact, they are sure to be unreliable. The nearer barrels approach the same uniformity of workmanship the nearer will they average alike in shooting qualities.

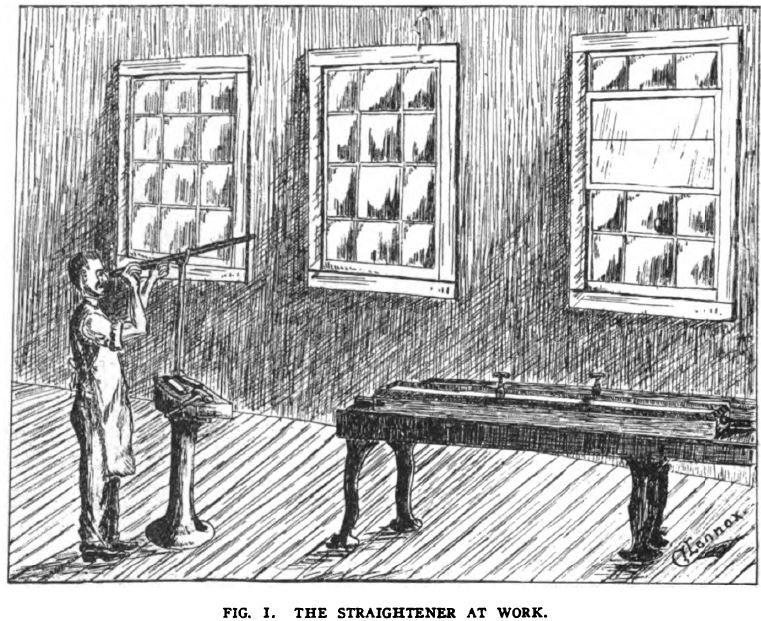

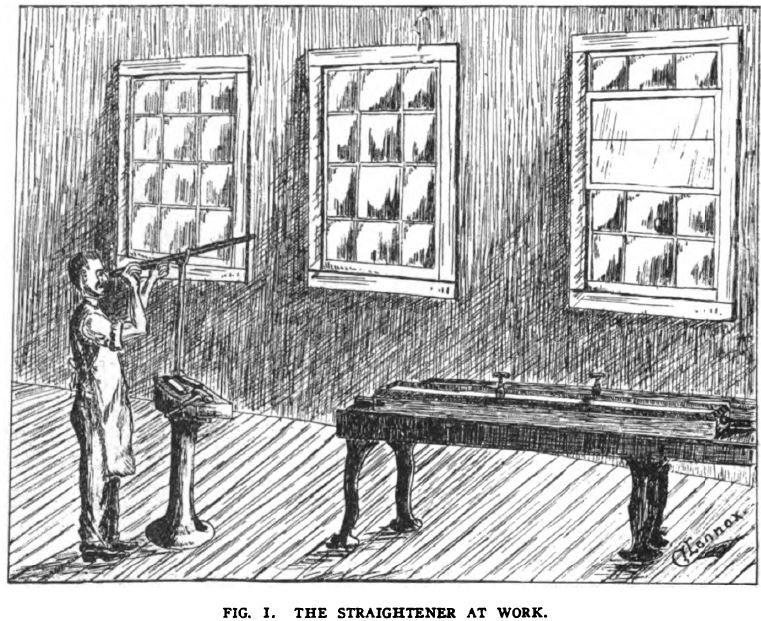

As the barrel is the most difficult part of the gun to make, just so is the straightening of the barrel the most difficult operation in its manufacture. No theoretical education is necessary in this branch of skilled labor, but there are certain physical requirements which are absolutely indispensable. Above all, the barrel straightener must be blessed by nature with strong and perfect eyesight. Weak eyes cannot possibly stand the strain, and sometimes strong ones deteriorate to the extent of compelling their owner to quit business. Then, again, the barrel straightener must be a man of fairly good judgment. It is very doubtful if there are one hundred persons engaged in this pursuit in the United States and Canada.

To become a first-class straightener, one should have not only perfect eyesight and natural ability, but also, where possible, constant practice on all varieties of barrels, as the difficulties attending the straightening operation vary according to the caliber and form of the barrel. The larger the bore and plainer the shape, the less the difficulty. Shotgun barrels not only require less skill in this operation, but there is not the strain on the eyes which attends the straightening of rifle barrels. The smaller the caliber, the greater the strain on eyesight, always. Extremely heavy barrels are more difficult to straighten than light ones. The least difficult in whatever caliber are those of soft steel and round shape; except where sight studs are brazed on nickel-steel barrels. All brazing crooks barrels to a greater or less extent, but soft steel is less affected than nickel. It is less difficult to straighten an octagon shaped barrel than one which is octagon for half its length and round the other half. Nickel-steel barrels, of whatever shape, are always more difficult to straighten than soft steel of any shape. Rapidity and excellence of workmanship determine the first-class expert in this line of work, the same as in all lines of human effort. He is the best who does his work the quickest and best.

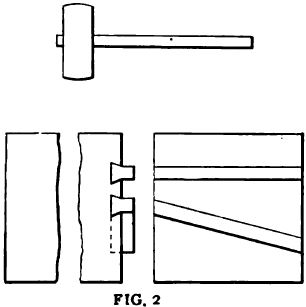

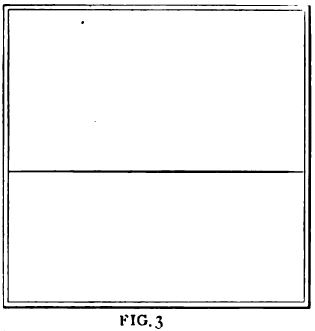

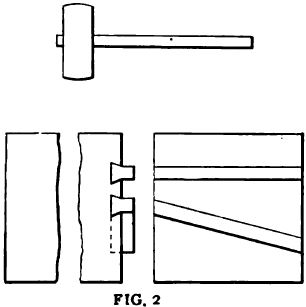

I will endeavor to explain the method of straightening, so that the reader may understand the operation. The tools used are three in number—a hammer, a block and a straightening shade. The hammer weighs from 3 ½ to 5 pounds, according to the workman's preference. Some use two hammers—a light one for light work and a heavy one for heavy work. The block, Fig. 2, is a square piece of soft steel, a foot square. It stands on an iron base about 3 feet high. Sunk in its face are two hardened steel dies; the front one is fixed straight across, and the rear one is at an angle. An iron rod at the back of the block holds the rest in which the operator places the barrel when sighting the shade in order to locate the crooks. The shade, Fig. 3, is a square of ground glass having a narrow line directly across the center. It is either set in the upper half of a window or suspended directly in front of one.

The narrow line across the shade casts the shadows down the bore of the barrel, which determine the degree of its straightness. These shadows are narrow and sharply defined. There is one on each side of the barrel, and they extend from the middle of the barrel outward to the end toward the shade. If the barrel is straight at that end, the shadows them selves will be straight; but if the barrel is crooked, the shadows will run in irregular lines—the greater the irregularity of the lines the more crooked the barrel. It is the straightener’s business to rectify this irregularity and make the lines run straight. When this has been accomplished on one end of the barrel the other end is corrected in precisely the same way. Thus, when the shadows run straight from the middle of the barrel to both ends, then the barrel is necessarily straight from one end to the other.

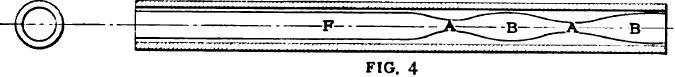

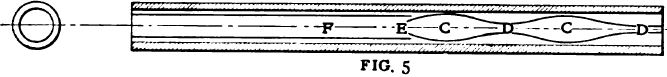

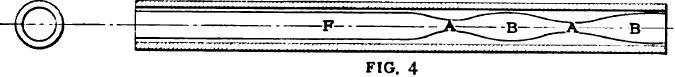

In order to demonstrate clearly the manner in which the straightening process is carried out. I refer the reader to Figs. 4 and 5, which give interior views of a gun barrel. Here it will be noticed that the irregular lines approach each other in some places and that they draw apart in others, as at A and B, Fig. 4.

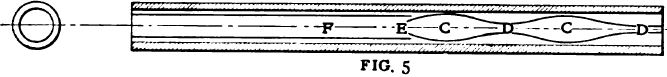

Now note Fig. 5, and it will be found that in identically the same places where the lines approach in Fig. 4 they diverge in Fig. 5, as at C. Again, at D, in Fig. 5, they approach, where at B, Fig. 4, they recede. This demonstrates the appearance of the lines to the practiced eye just below and just above the center of the bore of the same barrel. That is, if the lines when caught below the center of the bore appear like Fig. 4, they will if caught above the center assume the opposite appearance indicated in Fig. 5, and vice versa. Some straighteners catch the lines below the center of the bore and some above. This is simply a matter of choice, and all tends to the same final result.

Wherever the lines in a barrel approach each other, the barrel must be struck in such a way as to cause the lines to spread and assume a straight appearance. This is done by placing the barrel across the block on the dies, with the place to be struck resting directly between the dies. Should a mistake he made and the barrel be struck where the lines spread, the straightener would have a more crooked proposition to contend with than ever. Or should the barrel be struck heavier than necessary in the proper place the result would be the same as if hit in the wrong place.

In straightening a barrel the straightener always begins on the middle crook, as E, Fig. 5, and works outward toward the end. This crook must be got out first.

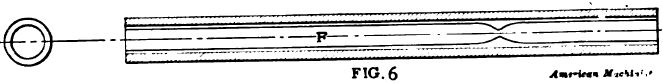

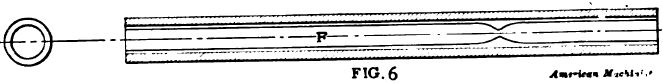

When the barrel has been successfully straightened, the lines will have a straight appearance, as at F. There is one exception, however, to this rule. Sometimes the shadows approach each other sharply, as in Fig. 6; no matter how the barrel may be turned the lines will look the same. This condition never indicates a crook. It is caused by a narrow ring, or low place, in the surface of the bore. The trouble is rectified by “setting in" the ring—a nice bit of work when properly done. The exact spot where the ring lies is located on the outside of the barrel and is struck round and round with the hammer, directly on top of a die. This, of course, depresses the outside of the barrel at that particular point, and raises the inside surface so that the ring soon stands higher than the regular surface of the bore. The barrel is then reamed, and if the operation has been properly performed the ring will disappear.

To be able to strike just the right blow in the right place is a matter which takes years of constant practice. A let-up, even for a few weeks, throws the straightener out of practice, and it takes some little time to get back into line again. In first class concerns new models are constantly coming to the front, and this causes the straightener no end of trouble through unending changes in the shape of the barrels.

In conclusion it should be stated that barrels are straightened from three to five times, according to the style of the barrel and the operations through which it must pass. Turning, milling, grinding, brazing, proving and filing all crook barrels more or less, and when they are crooked it is necessary that they be straightened.

By William H. Avis.

American Machinist, July 13, 1905, pages 44-45

https://books.google.com/books?id=x...=onepage&q=Line straightening barrels&f=false

It is conceded by gunmakers that the most difficult part of a gun to make is the barrel. If the interior of the barrel is incorrect the whole gun is liable to prove worthless. This does not necessarily mean that the bore must be absolutely perfect. But the nearer the workmanship approaches that standard the better. It is true that a barrel can sometimes be more or less defective and shoot very accurately; but this is the exception and not the rule. Defective articles, of whatever description, are not apt to be sought after, nor can they be depended upon; in fact, they are sure to be unreliable. The nearer barrels approach the same uniformity of workmanship the nearer will they average alike in shooting qualities.

As the barrel is the most difficult part of the gun to make, just so is the straightening of the barrel the most difficult operation in its manufacture. No theoretical education is necessary in this branch of skilled labor, but there are certain physical requirements which are absolutely indispensable. Above all, the barrel straightener must be blessed by nature with strong and perfect eyesight. Weak eyes cannot possibly stand the strain, and sometimes strong ones deteriorate to the extent of compelling their owner to quit business. Then, again, the barrel straightener must be a man of fairly good judgment. It is very doubtful if there are one hundred persons engaged in this pursuit in the United States and Canada.

To become a first-class straightener, one should have not only perfect eyesight and natural ability, but also, where possible, constant practice on all varieties of barrels, as the difficulties attending the straightening operation vary according to the caliber and form of the barrel. The larger the bore and plainer the shape, the less the difficulty. Shotgun barrels not only require less skill in this operation, but there is not the strain on the eyes which attends the straightening of rifle barrels. The smaller the caliber, the greater the strain on eyesight, always. Extremely heavy barrels are more difficult to straighten than light ones. The least difficult in whatever caliber are those of soft steel and round shape; except where sight studs are brazed on nickel-steel barrels. All brazing crooks barrels to a greater or less extent, but soft steel is less affected than nickel. It is less difficult to straighten an octagon shaped barrel than one which is octagon for half its length and round the other half. Nickel-steel barrels, of whatever shape, are always more difficult to straighten than soft steel of any shape. Rapidity and excellence of workmanship determine the first-class expert in this line of work, the same as in all lines of human effort. He is the best who does his work the quickest and best.

I will endeavor to explain the method of straightening, so that the reader may understand the operation. The tools used are three in number—a hammer, a block and a straightening shade. The hammer weighs from 3 ½ to 5 pounds, according to the workman's preference. Some use two hammers—a light one for light work and a heavy one for heavy work. The block, Fig. 2, is a square piece of soft steel, a foot square. It stands on an iron base about 3 feet high. Sunk in its face are two hardened steel dies; the front one is fixed straight across, and the rear one is at an angle. An iron rod at the back of the block holds the rest in which the operator places the barrel when sighting the shade in order to locate the crooks. The shade, Fig. 3, is a square of ground glass having a narrow line directly across the center. It is either set in the upper half of a window or suspended directly in front of one.

The narrow line across the shade casts the shadows down the bore of the barrel, which determine the degree of its straightness. These shadows are narrow and sharply defined. There is one on each side of the barrel, and they extend from the middle of the barrel outward to the end toward the shade. If the barrel is straight at that end, the shadows them selves will be straight; but if the barrel is crooked, the shadows will run in irregular lines—the greater the irregularity of the lines the more crooked the barrel. It is the straightener’s business to rectify this irregularity and make the lines run straight. When this has been accomplished on one end of the barrel the other end is corrected in precisely the same way. Thus, when the shadows run straight from the middle of the barrel to both ends, then the barrel is necessarily straight from one end to the other.

In order to demonstrate clearly the manner in which the straightening process is carried out. I refer the reader to Figs. 4 and 5, which give interior views of a gun barrel. Here it will be noticed that the irregular lines approach each other in some places and that they draw apart in others, as at A and B, Fig. 4.

Now note Fig. 5, and it will be found that in identically the same places where the lines approach in Fig. 4 they diverge in Fig. 5, as at C. Again, at D, in Fig. 5, they approach, where at B, Fig. 4, they recede. This demonstrates the appearance of the lines to the practiced eye just below and just above the center of the bore of the same barrel. That is, if the lines when caught below the center of the bore appear like Fig. 4, they will if caught above the center assume the opposite appearance indicated in Fig. 5, and vice versa. Some straighteners catch the lines below the center of the bore and some above. This is simply a matter of choice, and all tends to the same final result.

Wherever the lines in a barrel approach each other, the barrel must be struck in such a way as to cause the lines to spread and assume a straight appearance. This is done by placing the barrel across the block on the dies, with the place to be struck resting directly between the dies. Should a mistake he made and the barrel be struck where the lines spread, the straightener would have a more crooked proposition to contend with than ever. Or should the barrel be struck heavier than necessary in the proper place the result would be the same as if hit in the wrong place.

In straightening a barrel the straightener always begins on the middle crook, as E, Fig. 5, and works outward toward the end. This crook must be got out first.

When the barrel has been successfully straightened, the lines will have a straight appearance, as at F. There is one exception, however, to this rule. Sometimes the shadows approach each other sharply, as in Fig. 6; no matter how the barrel may be turned the lines will look the same. This condition never indicates a crook. It is caused by a narrow ring, or low place, in the surface of the bore. The trouble is rectified by “setting in" the ring—a nice bit of work when properly done. The exact spot where the ring lies is located on the outside of the barrel and is struck round and round with the hammer, directly on top of a die. This, of course, depresses the outside of the barrel at that particular point, and raises the inside surface so that the ring soon stands higher than the regular surface of the bore. The barrel is then reamed, and if the operation has been properly performed the ring will disappear.

To be able to strike just the right blow in the right place is a matter which takes years of constant practice. A let-up, even for a few weeks, throws the straightener out of practice, and it takes some little time to get back into line again. In first class concerns new models are constantly coming to the front, and this causes the straightener no end of trouble through unending changes in the shape of the barrels.

In conclusion it should be stated that barrels are straightened from three to five times, according to the style of the barrel and the operations through which it must pass. Turning, milling, grinding, brazing, proving and filing all crook barrels more or less, and when they are crooked it is necessary that they be straightened.